Chief Shingwaukonse did not like what he saw.

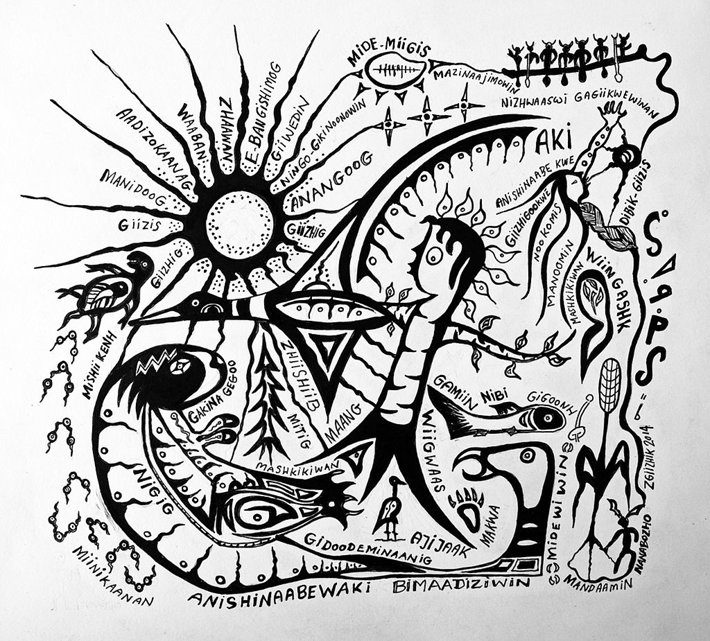

His people, the Anishinaabe, were being usurped, cheated of mino-bimaadiziwin—the way of the good life—by prospectors eager for the rich copper deposits on their lands on the Canadian side of Lake Superior. The colonial government granted mining licenses willy-nilly in the name of the British Crown, but the land was not the Crown’s to manage, supervise or administer.

In that year of 1848, the large swath of territory marked UNSURRENDERED on contemporary maps had never been ceded to anyone and still belonged to the Indigenous peoples who had dwelled there for centuries.

But now, the chief observed, the “animals of the woods” were vanishing—and his people depended on them for food, clothing and a hundred other things. The settlers, moreover, set fires to the forests, hastening the disintegration of this way of life. Shingwaukonse knew his people would not sit idle and watch their culture, lifestyle and identity be snatched away. He was right.

The following year a copper mine was taken over and occupied by a group of Indigenous people. Troops were called in and negotiations—long overdue—began.

William Benjamin Robinson, representing Queen Victoria, hammered out two treaties with the Anishinaabe where they agreed “fully, freely and voluntarily” to cede their territory to Queen Victoria and her heirs and successors. In return, they would retain hunting and fishing rights, and the Crown would pay them a perpetual annuity. A small one.

But the treaties promised more, far more. A key clause provided that if the land produced in the future an amount that would allow the government “without incurring loss, to increase the annuity,” then it “shall” be increased “from time to time.”

The first—and only—increase came in 1875, after Indigenous protests. It has remained at 4 Canadian dollars per person, nearly $3 U.S., ever since.

In the ensuing century and a half, while the treaties accumulated cobwebs, the now-former British colony of Canada benefitted a thousand-fold from the rich lands north of the Great Lakes while the First Nation peoples languished.

Those broken treaties became the subject of a key lawsuit that began in the 1990s and has just now been resolved.

Raymond Goodchild, who grew up in a tar paper shack and slept on a mattress taken from a dump, testified in an Ontario court that the British Crown’s broken promises left Indigenous people like himself impoverished.

He lived in the shadow of the prosperous boom town, Thunder Bay—a place of paved streets, beautiful houses with well-tended lawns.

“My God almighty … I still envy those people that had those houses,” Goodchild, 67, a veteran of the Canadian Armed Forces, testified last year in Sudbury, Ontario. He would walk by them and say to himself, “Wow, what a world—a completely different world from where I came from.”

In 2018, Ontario Superior Court Justice Patricia Hennessy ruled that the promises of the Robinson treaties had been “completely forgotten” by the Crown and that the court had the “authority and the imperative” to impose duties on it. The ruling was appealed. The appeals court mostly upheld it.

The case has been closely watched since the outcome could set the standard on how future cases of compensation to First Nation tribes are managed.

At this point, no one on either side disagrees that the Indigenous people got a raw deal. And this past November the province of Ontario admitted that it hadn’t kept its promise to Chief Shingwaukonse and his people. The remaining point: the price tag.

The government—predictably—prefers a low-ball figure: $1.8 billion, adding that it has no legal obligation to pay anything, really, partly because of its own expenses of billions of dollars over the decades that went to infrastructure and development. Besides, the government argued, financial redress is something that is not for a judge to order.

The First Nations groups disagreed. “After 173 years of government neglect and inattention, it is only fair and just for the chickens to come home to roost,” their cocounsel Harley Schachter countered.

And, another cocounsel, Kaitlyn Lewis, added the agreement “wasn’t sort of living in squalor” while settlers lived “lives of plenty.”

The plaintiffs presented their own figure, based on an economic model computed by Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz: $90 billion. “If you’ve owed somebody something year after year after year for 170 years, it’s a lot of money,” he said.

As a child, Wilfred King, chief of Gull Bay First Nation, heard the grown-ups talk about the Robinson treaties. He didn’t grasp their importance and the generations-long devastation left in their wake until he was older.

“We’ve been kept in abject poverty,” he said. “Our people are living in a very, very dire situation. Those treaties, had they been implemented initially, First Nations would have probably been in a much better position than they are today.”

Patricia Tangie, chief of the Michipicoten First Nation—who watches trucks carry resources from her lands while her own people live in poverty, inadequate housing, no paved roads and no nearby medical care—said the long court battle has left her feeling that “Canada has no commitment to reconciliation.”

“They say the words. They have all the nice words,” she said. “But there’s no action.”

Then, on January 3 action happened. All parties signed the settlement: $10 billion. Now a done deal, the First Nation signatories of the original 19th-century treaty should see the beginning flow of the long-delayed funds as early as this spring.

Through the settlement, albeit a long time coming, a great many people, living and dead, will reap a measure of justice.

And through the great spiritual bond of past, present and future, maybe, just maybe, old Chief Shingwaukonse—that Midewiwin who watches over his people still—will find a measure of peace at last.

_________________

From its beginnings, the Church of Scientology has recognized that freedom of religion is a fundamental human right. In a world where conflicts are often traceable to intolerance of others’ religious beliefs and practices, the Church has, for more than 50 years, made the preservation of religious liberty an overriding concern.

The Church publishes this blog to help create a better understanding of the freedom of religion and belief and provide news on religious freedom and issues affecting this freedom around the world.

The Founder of the Scientology religion is L. Ron Hubbard and Mr. David Miscavige is the religion’s ecclesiastical leader.

For more information, visit the Scientology website or Scientology Network.